Dangerous Words from Nariaki Tokugawa & Shoin Yoshida;

Printed by Movable Type

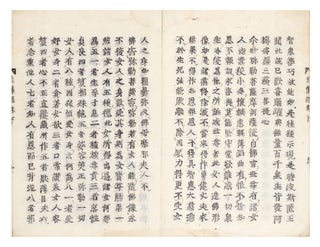

Broadside on paper (228 x 334 mm.), mounted on a hanging scroll, printed with wooden movable type, entitled Mito Nariaki kyo hekisho [Words for the Students by the Honorable Nariaki of Mito].

Shoka Sonjuku Academy, Hagi, Yamaguchi Prefecture: Printed by (in trans.) “movable [type],” 1858.

An extremely rare and unusual example of movable wooden type printing in Japan. Movable type books enjoyed a considerable popularity in Japan in the first four decades of the 17th century, but gradually this technology withered away in favor of xylography. The use of wooden movable type was revived again in the late 18th century for small private editions, oftentimes to print controversial texts and issued sub rosa. The texts of some of these works might have faced censorship if commercially published. These kinds of movable type printings from after 1653 are called mokkatsujiban (for a fascinating discussion, see Kornicki, The Book in Japan, pp. 159-63).

The present broadside is just such an example. It was printed at the famous Shoka Sonjuku (“village school under the pines”), in the castle town of Hagi in Yamaguchi Prefecture. This school produced, in a two-year period, some 70 future leaders who contributed to the Meiji Restoration and the development of modern Japan, including two prime ministers. Its dynamic principal and main teacher at that time was the magnetic Shoin Yoshida (1830-59), educator, scholar, and political activist. He had studied Western and Chinese military strategy and science and openly supported the emperor against the shogunate. In 1854, he and a friend, Jusuke Kaneko, tried to stow away on Commodore Perry’s flagship, the Powhatan, anchored off Shimoda. Perry refused, and the two young men were imprisoned by the shogunal authorities. Kaneko soon died, but Yoshida was released in January 1856 and, while under house arrest, soon became principal of the Shoka Sonjuku, which was owned by his uncle. During his brief tenure there, Shoin attracted an extraordinary group of future leaders. Through lectures and his many writings (memorials, proposals, and letters to his students), he “deplored the superficiality of upper samurai life at a time of national danger, and proposed that the domain ignore rank, and even status, in its appointments. If the country was to be opened he wanted the bakufu to do it actively and purposefully, rather than, as it seemed, cravenly and hesitantly. Students should be sent abroad to each country; Japan should have a fleet, and trade, and become a presence on the world stage instead of remaining a victim.”–Jansen, The Making of Modern Japan, p. 293. However, during the Ansei purge in 1859, Yoshida was arrested and beheaded. He is considered one of the intellectual fathers of modern Japan.

This broadside, printed by movable type at the school, contains two dangerous texts, both very much in the Mitogaku tradition, one of the driving forces behind the Meiji Restoration. On the right side, we find five instructions of moral guidance by Nariaki Tokugawa (1800-60), the one-time lord of Mito fiefdom, who supported loyalty to the emperor, war with foreigners, and devotion to the sonno-joi movement (“revere the emperor, expel the foreigners”). Nariaki had founded his own academy, the Kodokan, to foster practical Western learning in order to defend the nation. Shoin’s earlier studies at Kodokan had reinforced his ideas of the future of Japan.

The five apothegms of Nariaki all concern the need to appreciate the military and its soldiers: one must be grateful to them and their sacrifices for the comforts civilians enjoy. The Japanese should thank the soldiers for food, clothes, homes, comfortable living conditions, and traditional social relations, all of which the members of the military had given up, in service to their country. These maxims are dated Spring 1854.

On the opposite side of the broadside, which is divided by a “pillar,” are Shoin Yoshida’s responses. In essence, he writes: “The incompetent government and their confusions must be ignored. Discipline yourself, behave ethically as an example to your family, and this behavior will spread to others. My students must learn from the words of Nariaki. Printed by movable [type].” At the start of Shoin’s comments is printed the zodiac date of “Winter 1857,” and at the close, the date “Good Day January 1858.” At the end, “Shoka Sonjuku” is printed.

PROVENANCE: This broadside has several manuscript notes in one hand. The first states (in trans.): “Selected and written by Nijuikkai sensei [=Shoin Yoshida].” Around the borders of the broadside, the same annotator has written, again in translation: “Mito Nariaki’s words in movable type. January 1858. Hagi. Shoka Sonjuku ban [edition].”

Accompanying this broadside is a sheet of notes by the next unnamed owner, who has written (in abbreviated & rough trans.): “Purchased from the family of Shoin’s disciple Chuzaburo Terashima [he was one of the closest followers of Shoin and died in the Hamaguri Gate Rebellion of 1864]. In the article in the journal Sonjuku sakumon ichido, dated 12 April 1858, we learn that the Shoka Sonjuku Academy was equipped with a wooden movable type press that was primitive and imperfect but highly valued. This broadside is rare and probably the only surviving example. Let us consider its historical and technological importance.”

We know that Shoin’s responses printed here are included in his collected works, Yoshida Shoin zenshu, printed in Tokyo in 1934-36 in ten volumes.

Our scroll is preserved in a wooden box, which has the inscription on the lid of Mr. Mori, the chief bibliographer to the great Japanese bookseller Shigeo Sorimachi. Mori has written (in trans.): “Words for the Students by Nariaki Tokugawa. Hagi. Shoka Sonjuku. Katsujiban [movable type].”

In fine condition.

❧ Maida Stelmar Coaldrake, “Yoshida Shoin (1830-1859) and the Shoka Sonjuku” (online Ph.D. thesis, 1985).

Price: $12,500.00

Item ID: 8120

![Item ID: 8120 Broadside on paper (228 x 334 mm.), mounted on a hanging scroll, printed with wooden movable type, entitled Mito Nariaki kyo hekisho [Words for the Students by the Honorable Nariaki of Mito]. SHOKA SONJUKU MOVABLE TYPE BROADSIDE.](https://jonathanahill.cdn.bibliopolis.com/pictures/8120.jpg?width=768&height=1000&fit=bounds&auto=webp&v=1649497487)

![Broadside on paper (228 x 334 mm.), mounted on a hanging scroll, printed with wooden movable type, entitled Mito Nariaki kyo hekisho [Words for the Students by the Honorable Nariaki of Mito].](https://jonathanahill.cdn.bibliopolis.com/pictures/8120_2.jpg?width=320&height=427&fit=bounds&auto=webp&v=1649497487)