Sakhalin is an Island

Manuscript on paper, entitled “Todatsu kiko” [“Travels in the Region of Eastern Tartary”].

14 double-page & three single-page fine brush & color-wash illus. 21, 19, 20 folding leaves. Three parts in one vol. Large 8vo (270 x 188 mm.), orig. semi-stiff blue patterned wrappers, manuscript title label on upper cover, new stitching. [Japan]: copied by Mokuro Kimura in Tenpo era (1830-44).

A very rare manuscript account of the two expeditions in 1808 and 1809 of Mamiya (1775-1844), hydraulic engineer, cartographer, and explorer, to survey Sakhalin Island (J: Kita Ezo or Karafuto), off the coast of Siberia. The “Todatsu kiko” is Mamiya’s main Sakhalin travel narrative. During these journeys, Mamiya discovered that Sakhalin is separated from the mainland by a strait, crossed it, and visited eastern Siberia in 1809, returning to Japan via China. “Todatsu kiko,” submitted by Mamiya to officials of the shogunate in March 1811, contains valuable geographical and ethnographic information, in which he describes many encounters with the Ainu, Orokko, Uilta, Nivkh, and Yakagir people. Much of our description is dependent on Prof. Brett L. Walker’s fine article “Mamiya Rinzo and the Japanese Exploration of Sakhalin Island: Cartography and Empire,” in Journal of Historical Geography, Vol. 33 (2007), pp. 283-313.

By the early 19th century, Sakhalin Island had become of considerable geopolitical and imperialistic interest to various nations, including Russia, Japan, France, and Britain. Several Western explorers had surveyed portions of its coast. At this time, it was uncertain whether Sakhalin was a peninsula or an island. In 1787, La Pérouse had determined that it was indeed an island, but this was based only on conversations with the natives. Mamiya was the first to actually see with his own eyes that Sakhalin was separated from Siberia by a substantial body of water, today known as the Mamiya Strait.

From the 18th century, Japan was interested in Sakhalin as part of its economic expansion into the north Pacific (the waters around the island were rich in herring and sea cucumbers, and the island also had considerable natural resources) and because of worry that the Ainu might defect to Russian-controlled areas and convert to Christianity. Japan also wished to control the active and valuable commercial network known as the “Santan” trade, which stretched from Qing posts along the Amur River region in Siberia to Ainu villages in southern Sakhalin and northern Hokkaido. In 1807, the Tokugawa government took control of Sakhalin from the Matsumae fiefdom and commissioned Mamiya to explore and cartographically record the island. The shogun sought to determine the national boundaries between Japan, Russia, and the Qing empire.

Mamiya, accompanied by his fellow explorer Denjiro Matsuda, arrived on Sakhalin in April 1808. They split up, each going up opposite sides of the island. Following a brief return to Hokkaido, Mamiya continued to explore Sakhalin through the early part of the summer of 1809. Afterwards, he sailed to Siberia, entering the mouth of the Amur River and navigating his way to the Qing outpost of Deren in July 1809. Later in the year Mamiya and Matsuda reunited at Shiranushi in southern Sakhalin.

Upon returning to Soya, the northernmost point of Hokkaido, Mamiya prepared the present report and drafted several maps of Sakhalin. These were considered to be of the greatest secrecy, and only a few copies of “Todatsu kiko” (apparently seven) were prepared in manuscript and retained for governmental use.

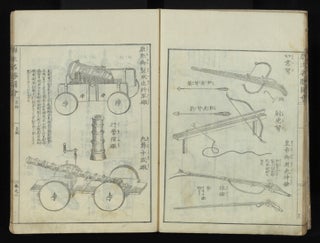

The first part of the manuscript describes Mamiya’s exploration, day by day, of Sakhalin Island and includes many place names. There are reports of the natives’ customs, attire, and habitats. There are fine illustrations of the Orokko tribal living quarters and one of their typical boats, which Mamiya judged to be rather flimsy.

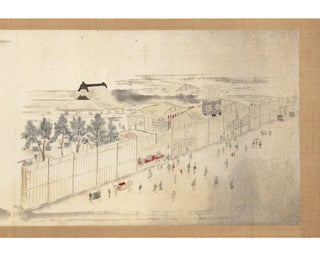

Parts Two and Three are concerned with Mamiya’s journey up the Amur River to the Chinese town of Deren. He describes the various tribal people he met on the way. Mamiya notes that there were 50 or 60 Qing officials in Deren along with Korean and Russian representatives. He communicated successfully with the Qing officials by writing in Chinese characters. There is a fine scene of boats, filled with trading goods, being rowed along the Amur River. Fortifications and living quarters for the Chinese are also depicted, along with illustrations of various Chinese officials of different ranks. In a wonderful scene we see an Ainu trader with furry animals under one arm about to exchange them with a Chinese dealer who is holding silk. There is also a fine market scene, a real “beehive” of activity, depicting Chinese traders carrying, offering, and exchanging goods.

The first double-page illustration in the third part shows a dinner party with two Qing officials, one Japanese (presumably Mamiya) being served a bowl of fish, and two Chinese servants. Next to the dining table is a bookcase with scrolls, books, and maps. Mamiya was surprised by the high level of education of the Qing officials.

PROVENANCE: Our manuscript bears on the first leaf the seal of Mokuro Kimura (1774-1856), a senior official of the Takamatsu fiefdom and man of letters and the arts. He formed a large library. We learn in a statement written by Kimura in 1836 on the final leaf that he gained access to one (he writes that there were seven) of the original manuscript copies of “Todatsu kiko.” That copy was owned by Kyosho Tachihara (1786-1840), a samurai and well-known nanga painter, who allowed Kimura to make this copy. On the recto of the final leaf, Kimura makes another statement, dated 1837, that he was enabled to gain access to one of the original manuscripts thanks to the efforts of Josui Ishikawa (1807-41), a government official.

The manuscript is loosely housed and protected by Chinese-style wooden boards, with an inscription on the upper board stating that this manuscript was copied by Kimura. On the inside of the upper board is an inscription stating that the wooden boards were made in 1913. The manuscript is further protected by thick paper wrappers.

In very fine condition. Unimportant small worming. WorldCat lists manuscript copies of this work at Harvard and American University.

Price: $19,500.00

Item ID: 7753

![Item ID: 7753 Manuscript on paper, entitled “Todatsu kiko” [“Travels in the Region of Eastern Tartary”]. Rinzo MAMIYA.](https://jonathanahill.cdn.bibliopolis.com/pictures/7753.jpg?width=768&height=1000&fit=bounds&auto=webp&v=1640430730)

![Manuscript on paper, entitled “Todatsu kiko” [“Travels in the Region of Eastern Tartary”].](https://jonathanahill.cdn.bibliopolis.com/pictures/7753_2.jpg?width=320&height=427&fit=bounds&auto=webp&v=1640430730)

![Manuscript on paper, entitled “Todatsu kiko” [“Travels in the Region of Eastern Tartary”].](https://jonathanahill.cdn.bibliopolis.com/pictures/7753_3.jpg?width=320&height=427&fit=bounds&auto=webp&v=1640430730)

![Manuscript on paper, entitled “Todatsu kiko” [“Travels in the Region of Eastern Tartary”].](https://jonathanahill.cdn.bibliopolis.com/pictures/7753_4.jpg?width=320&height=427&fit=bounds&auto=webp&v=1640430730)

![Manuscript on paper, entitled “Todatsu kiko” [“Travels in the Region of Eastern Tartary”].](https://jonathanahill.cdn.bibliopolis.com/pictures/7753_5.jpg?width=320&height=427&fit=bounds&auto=webp&v=1640430730)

![Manuscript on paper, entitled “Todatsu kiko” [“Travels in the Region of Eastern Tartary”].](https://jonathanahill.cdn.bibliopolis.com/pictures/7753_6.jpg?width=320&height=427&fit=bounds&auto=webp&v=1640430730)

![Manuscript on paper, entitled “Todatsu kiko” [“Travels in the Region of Eastern Tartary”].](https://jonathanahill.cdn.bibliopolis.com/pictures/7753_7.jpg?width=320&height=427&fit=bounds&auto=webp&v=1640430730)

![Manuscript on paper, entitled “Todatsu kiko” [“Travels in the Region of Eastern Tartary”].](https://jonathanahill.cdn.bibliopolis.com/pictures/7753_8.jpg?width=320&height=427&fit=bounds&auto=webp&v=1640430730)

![Manuscript on paper, entitled “Todatsu kiko” [“Travels in the Region of Eastern Tartary”].](https://jonathanahill.cdn.bibliopolis.com/pictures/7753_9.jpg?width=320&height=427&fit=bounds&auto=webp&v=1640430740)

![Manuscript on paper, entitled “Todatsu kiko” [“Travels in the Region of Eastern Tartary”].](https://jonathanahill.cdn.bibliopolis.com/pictures/7753_10.jpg?width=320&height=427&fit=bounds&auto=webp&v=1640430740)

![Manuscript on paper, entitled “Todatsu kiko” [“Travels in the Region of Eastern Tartary”].](https://jonathanahill.cdn.bibliopolis.com/pictures/7753_11.jpg?width=320&height=427&fit=bounds&auto=webp&v=1640430740)