The First to Use the Term Mineralogy in the

Modern Sense

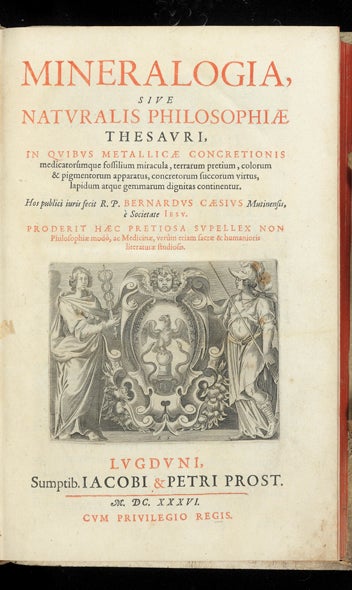

Mineralogia, sive Naturalis Philosophiae Thesauri, in quibus Metallicae Concretionis medicatorúmque fossilium miracula, terrarum pretium, colorum & pigmentorum apparatus, concretorum succorum virtus, lapidum atque gemmarum dignitas continentur.

Large engraved vignette on title. Title in red & black. 8 p.l., 626, [69] pp. Folio, cont. blind-stamped pigskin over wooden boards, arms on covers effaced. Lyon: J. & P. Prost, 1636.

First edition, Schuh’s issue B (no stated priority) with the dedication to Charles de Neufville. “Very scarce. Compendium of all the author ever discovered or read about the subject of mineralogy. It was published posthumously from notes he left by his Order at Lyon six years after his death. Printed in a double column format in a relatively small type-size, the work is a vast storehouse of all things mineralogical, including new ideas, restatements of earlier authors, observations and superstitious belief. The uncritical selection of material led Webster in his Metallographia (London, 1671, p. 29) to criticize the author as too digressive and as mixing tares with the wheat. Partington thinks the use of the term ‘Mineralogia’ in the title is the first modern usage of the word…

“The work opens by listing the evils and benefits of mineralogy. Mining is considered dangerous because of the lurking underground spirits…the author notes that the study of mineralogy helps one to understand the bible. It provides medicines and money, ornaments for religious purposes, tools used in agriculture, industry, painting, music and alchemy. Cesi then answers the question he posed earlier and declares mineralogy to be a true philosophy, worthy of careful study…

“The numerous citations to earlier authors provide evidence of Cesi’s wide reading. Commonly, many authors are referenced on single points. For example, in describing the generation of minerals he closely follows Aristotle but also cites Theophrastus, Avicenna, Albertus Magnus, Agricola, Gregorius Reisch, Pliny, Boodt, Francis Rueus, Marbode, the Bible, and numerous church fathers. The author is uncritical of the views he presents, and accepts the authority of the ancient and medieval authors as his own. He believes that the Sun, Moon and stars influence the subterranean world of minerals and metals, and that gems have miraculous curative powers. He includes a chapter on the magnet…

“Cesi divides his work into five sections: the first treats mineralogy proper, the second the economic and commercial aspects, for example colors and pigments, the third, lapidifying juices of the earth that congeal into minerals, the fourth gems and the fifth metals. At the conclusion is a long and thankfully comprehensive index. Much insight about ancient philosophy and its affect in the 17th century can be gained from studying Cesi’s Mineralogia.”–Schuh, Mineralogy & Crystallography: A Biobibliography, 1469 to 1920, pp. 358-59.

Cesi (1581-1630), was a Jesuit professor at Modena and Parma.

A nice copy of a book which is now scarce on the market.

❧ Hoover 214. Partington, II, p. 94. Schuh 1113. Sinkankas 1221–(who, inaccurately, calls this issue a reprint. Sinkankas knew mineralogy very well but nothing about bibliography). Thorndike, VII, pp. 254-57.

Price: $9,500.00

Item ID: 3396

![Hinaasobi no ki [trans.: About the Hina Doll Play]; title for Vol. II: Kaiawase no ki [trans.:. Naokata NAKANISHI, or WATARAI.](https://jonathanahill.cdn.bibliopolis.com/pictures/6330.jpg?width=320&height=427&fit=bounds&auto=webp&v=1538008527)